Identities and the Media: Reading the riots

- How did the language and selection of images in the coverage create a particular representation of young people?

They described them as ‘riots’ rather than, for example, ‘civil disturbances’ or ‘unrest’ – or even ‘uprisings’ or ‘protests’ – the word 'riots' immediately appeared on at least five front pages following the first day of the disturbances, and in many reports since. The word riot suggests something wild and unrestrained, something fundamentally irrational that cannot be explained. The riots, we were told, were simply an ‘orgy of brutality’, in which people appeared to lose all rational control. The newspapers consistently featured large, dramatic images of what the Daily Mirror called ‘young thugs with fire in their eyes and nothing but destruction on their mind’, or the Daily Express called simply ‘flaming morons’. There was a iconic image of one black, hooded young man which appeared on at least five front pagesIn most of the tabloid media coverage, the rioters were consistently and repeatedly identified as young people. Many of the people convicted for crimes during the rioting were not even young. Just a few weeks later, young people achieved record passes in their GCSE and A Level exams. Those involved in the disturbances were obviously a small minority. Yet in much of the media coverage, they came to stand for Young People.

- Why does David Buckingham mention Owen Jones and his work Chavs: the demonisation of the working class?

Owen Jones argues that the working class have become an object of fear and ridicule. Therefore, David Buckingham mentions his work to show how despite this, many of those ultimately convicted after the rioting were in respectable middle-class jobs, or from wealthy backgrounds. There were incredulous press reports of an estate agent, an Oxford graduate, a teachers’ assistant, a ballerina and an army recruit– not to mention a doctor’s daughter, an Olympic ambassador and a church minister’s son – who all appeared in court.

- What is the typical representation of young people – and teenage boys in particular? What did the 2005 IPSOS/MORI survey find?

A 2005 IPSOS/MORI survey found that 40% of newspaper articles featuring young people focused on violence, crime or anti-social behaviour; and that 71% could be described as having a negative tone. Research from Brunel University during 2006 found that television news reports of young people focused overwhelmingly either on celebrities such as footballers or (most frequently) on violent crime; while young people accounted for only 1% of the sources for interviews and opinions across the whole sample.

More recently, a study by the organisation

Women in Journalism analysed 7,000+ stories

during 2008.

72% were negative- o

ver 75%

were about crime, drugs, or police: the great

majority of these were negative, while

only a handful were positive (0.3%).

Even for

the minority of stories on other topics such as

education, sport and entertainment, there were

many more negative than positive stories (42%

versus 13%).

Many of the stories about teenage

boys described them using disparaging words

such as yobs, thugs, sick, feral, hoodies, louts,

heartless, evil, frightening and scum.

- How can Stanley Cohen’s work on Moral Panic be linked to the coverage of the riots?

In a moral panic, he writes:

a threat to societal values and interests; its nature is presented in a stylized and stereotypical fashion by the mass media; the moral barricades are manned by editors, bishops, politicians and other right-thinking people; socially accredited experts pronounce their diagnoses and solutions; ways of coping are evolved or (more often) resorted to; the condition then disappears, submerges or deteriorates and becomes more visible.

A condition, episode, person or group of

persons emerges to become defined as

Cohen also argues that the media play a role in ‘deviance amplification’: in reporting the riots and by expressing the fear and outrage of ‘respectable society’, they make it more

Media stereotypes are never simply inaccurate: they always contain a ‘grain of truth’. Yet in this case, the media coverage can be seen to reflect a

attractive to those who might not otherwise have

thought about becoming involved.

much more general fear of young people (and

especially of working-class young people) that

is very common among many adults: the media

speak to anxieties that many people already have.

- What elements of the media and popular culture were blamed for the riots?

In the tabloid press, much of the initial blame for the violence was put on popular culture: it was rap music, violent computer games or reality TV that was somehow provoking young people to go out and start rioting.

trashy materialism and raves about drugs.

Others suggested that the looting of sportswear shops had been inflamed by advertising – it was like Supermarket Sweep,

The Daily Mirror, for example, blamed

the pernicious culture of hatred around rap

music, which glorifies violence and loathing

of authority (especially the police but

including parents), exalts

said the Daily Mail; while images of looters posing for the cameras and displaying their pickings were seen as evidence of the narcissism and consumerism of the ‘Big Brother and X Factor generation’.

Blaming the media is a common aspect of moral panics. There’s a very long history of the media being blamed for young people’s misbehaviour, which can be tracked back from current concerns about videogames or the

internet to earlier fears about the influence

of television and the cinema.

- How was social media blamed for the riots?

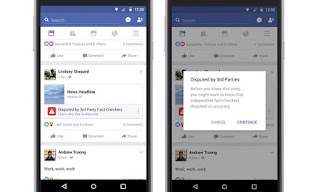

Rioters were seen as somehow skilful enough to co-ordinate their actions by using Facebook, Blackberry and Twitter. The Sun, for example, reported that ‘THUGS used social network Twitter to orchestrate the Tottenham violence and incite others to join in as they sent messages urging: ‘Roll up and loot’.

According to The Telegraph: technology fuelled Britain’s first 21st century riot. The Tottenham riots were orchestrated by teenage gang members, who used the

- What was interesting about the discussion of social media when compared to the Arab Spring in 2011?

There was discussion about the use of social networking in the revolutions that took place in countries such as Tunisia, Egypt and Syria.

These observations in turn caused some –

such as Tottenham MP David Lammy – to call

for companies like Blackberry to suspend their

services. Some even argued

that the police might be empowered to ‘turn off

the internet’ at the first sign of trouble. Once

again, the media were identified as a

primary cause of what took place – as though

riots and revolutions were simply created by the

use of technology.

- What were the right-wing responses to the causes of the riots?

An article by Daily Mail, headed ‘Years of liberal dogma have spawned a generation of amoral, uneducated, unparented, welfare dependent, brutalised youngsters’. they carry on and state that the working-class youth – apparently live lives of ‘absolute futility’: They are essentially wild beasts. They use that phrase because it seems appropriate to young people bereft of the

discipline that might make them employable;

of the conscience that distinguishes

between right and wrong. They respond

only to instinctive animal impulses — to

eat and drink, have sex, seize or destroy

the

For some right-wing commentators, it is

parents who are principally to blame for this

situation; while others, such as Katharine

Birbalsingh, blame schools for failing to instil

discipline and respect for authority – especially,

according to her, in black children. For some, this

failure even extends to the police – as for one

Daily Telegraph letter writer, who argued that the r

iots were ‘a result of the police caring more for

community relations than for the rule of law’.

Framing the issue in this way, as a failure

of discipline, thus inevitably leads to a call for

disciplinary responses.

- What were the left-wing responses to the causes of the riots?

They point out that the UK has

one of highest levels of inequality in the Western

world. They argue that it was unsurprising that

most of the disturbances erupted in areas with

high levels of poverty and deprivation – and, they

point out, it was tragic that these communities

also bore the brunt of the damage.

More specifically, they point to the cuts in

youth services (Haringey, the borough in which

Tottenham is located, recently closed 8 of its

13 youth clubs), rising youth unemployment

and the removal of the Education Maintenance

Allowance. While these are valid arguments, they

also appear to look only to youth as the cause.

- What are your OWN views on the main causes of the riots?

I agree with the left-wing response. T

he cuts in youth services and the removal of the Education Maintenance Allowance meant that young people didn't have anything to do and didn't have the money to go out so they used the riots as a way to socialise and the theft meant that they were getting money.

- How can capitalism be blamed for the riots? What media theory (from our new/digital media unit) can this be linked to?

Capitalism can be considered to be the blame for the riots due to the fact that the ruling class may have

influenced the youth to act out since they are always lying and cheating in order to gain power and wealth. The youth decided to riot since they had nothing to lose. A theory that can be linked to the capitalism within the riots can be the theory of hegemony as the elite, ruling class often construct, control and dominate the ideologies to make society believe and fall into the trap that they are normal, however the youth began to fight back against the hegemonic, traditional ideologies.

- Were people involved in the riots given a voice in the media to explain their participation?

Participants in the riots were not given a opportunity to explain why or how the joined into the riots. Despite this, 3rd parties, like historians explained the riots. This may have given some information, but for the society and citizens to get a more clear and honest view on the riots, there wouldn't have been a better way than to use a participant. One reason as to why some rioters may have not been given the opportunity is because they may aim to challenge the ideologies set by the ruling class.

- In the Guardian website's investigation into the causes of the riots, they did interview rioters themselves. Read this Guardian article from their Reading the Riots academic research project - what causes are outlined by those involved in the disturbances?

Some of the causes outlines in the guardian article were:

- Social media wasn't used in significant way but BBM was used

- Materialistic desires

- Unemployment

- Looting was down to opportunity

- Political grievances

- Gang members only played a marginal role

- What is your own opinion on the riots? Do you have sympathy with those involved or do you believe strong prison sentences are the right approach to prevent such events happening in future?

In my view, I can understand why the youth rioted. I believe everyone has morals, but some get pulled into the thought that violence is the key to solving these issues. In fact, violence only makes them worse. I have sympathy in the aspect that these youths aren't been given a fair opportunity in order to succeed as there are continuously barriers put in place in order to make it harder for them. However, if they wish to become successful, they need to realise that violence and chaos won't get them anywhere.